The Original of Laura, by Vladimir Nabokov (Penguin Modern Classics). This is my first blog post in a wee while. and I’m ashamed to say that it’s because I’ve been drawn into the world of young adult fiction. Namely the Divergent trilogy: Divergent, Insurgent and Allegiant. I thought that, after my Hunger Games post, folk might not be interested in reading another review on a teenage angst trilogy. If I’m wrong, by all means let me know and I will write that review! But anyway, today I will be rambling on a bit about The Original of Laura by Nabokov, his last, unfinished novel about the seductive Laura, or ‘Flora’ as is her real name. She is immortalised in fiction by one of her many lovers, and the knowledge of her infidelity drives her husband to self-destruction.

A short description of her appears at the beginning of the book, and it beautifully highlights the way that the reality of Laura intermingles with the fiction that has been invented:

She was an extravagantly slender girl. Her ribs showed. The conspicuous knobs of her hipbones framed a hollowed abdomen, so flat as to belie the notion of “belly.” Her exquisite bone structure immediately slipped into a novel – became in fact the secret structure of that novel, besides supporting a number of poems.

I don’t know if, had Nabokov had more time to finish the novel, he would have revealed more of this woman to us, or if the whole point is that she never gives herself wholly to any one person. She seems fragmented, illusive. Not entirely likeable, but that’s not the point.

The novel has been published, admittedly, against the author’s will, as he requested that the work be destroyed if he were to die before completion. His wife agreed to this, but never managed to fulfill the promise. Nabokov’s son, Dmitri, writes extensively in the introduction to the book on his decision to publish against his father’s will. He explains that it was entirely likely that his father did not believe that Vera, his wife, would be able to destroy the manuscript (as she had rescued an early draft of Lolita from the fire in the past) and that he knew that the book would eventually be published. I feel torn with regard to this. On one hand I think that the author should decide whether or not their work ever sees the light of day, but on the other hand I can’t imagine a world without Lolita, and it would have been burned if Vlad had had his way. It’s so tricky to know what the right thing is.

Having read The Original of Laura, I can see why Nabokov might have made such a request. His writing style is not one that lends itself to a posthumous publication. He seems to just write things as they come into his head, constantly adding notes to himself, and reproducing copy at different stages in the manuscript to work out where it should appear in the final piece. Solely taking this into consideration, I would argue that Dmitri had no right publishing the book at all, as it isn’t an accurate representation of Nabokov’s work and skill – the final piece pales in comparison to Pale Fire and Lolita.

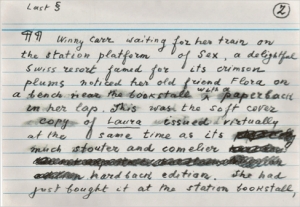

However, there was another reason to publish the book. Dmitri has given an insight into his father’s life as a writer, and has also reproduced the index cards with Nabokov’s scrawled notes and writing. It’s fascinating to be able to closely inspect his writing process, to see the words scrubbed out and replaced with better alternatives, the underlined phrases that he deemed important for some reason or other. It adds a whole new layer to textual analysis. The book even has serrated pages, so you can remove the index cards and rearrange them as Nabokov probably did.

However, there was another reason to publish the book. Dmitri has given an insight into his father’s life as a writer, and has also reproduced the index cards with Nabokov’s scrawled notes and writing. It’s fascinating to be able to closely inspect his writing process, to see the words scrubbed out and replaced with better alternatives, the underlined phrases that he deemed important for some reason or other. It adds a whole new layer to textual analysis. The book even has serrated pages, so you can remove the index cards and rearrange them as Nabokov probably did.

It’s definitely worth a read, not only for the romantic and delectable turns of phrase so unique to Nabokov, but also for the fascinating insight into the author’s thought process. Any Nabokov fan should have Nabokov’s last novel on their bookshelf.

Right, cost. I have talked about this in passing before, but this gives me the opportunity to have a good rant. For many of the cannonical classics there is no living author, and often no rights either. Thus, if I wanted to, I could typeset, print, bind and sell a copy of Great Expectations tomorrow and wouldn’t have to pay anyone (If I did all the production). So how is it that companies (Cambridge Modern Classics and Penguin Classics being the big players here) can rationalise a £9.99 price tag (going all the way up to around £17 in some cases) for a book where there is no advance or royalty needing covered?

Right, cost. I have talked about this in passing before, but this gives me the opportunity to have a good rant. For many of the cannonical classics there is no living author, and often no rights either. Thus, if I wanted to, I could typeset, print, bind and sell a copy of Great Expectations tomorrow and wouldn’t have to pay anyone (If I did all the production). So how is it that companies (Cambridge Modern Classics and Penguin Classics being the big players here) can rationalise a £9.99 price tag (going all the way up to around £17 in some cases) for a book where there is no advance or royalty needing covered?

The Hearing Trumpet, by Leonora Carrington

The Hearing Trumpet, by Leonora Carrington